The Key to Survival: Odd Vegetables?

Last week, we got kohlrabi in our CSA boxes for a second time in a row. Chatting with a fellow CSA* member she complained, “Why did we get kohlrabi again? Can’t they just give us vegetables we know?”

Our personal vegetable kingdoms are frequently divided between “vegetables we know” and “everything else.” The former category includes perennial favorites like tomatoes, lettuce, cucumbers and peppers. The latter is a dumping ground for those vegetables we never buy or that don’t have instant taste appeal–like kohlrabi, collards, radishes, turnips, parsnips and celeriac.

Why go to the effort of growing, buying and cooking all these odd vegetables? If we can go to the store and buy easy things like carrots and spinach, why bother with produce that presents such preparation and palatability challenges? It’s a fair question, and I’ve often asked it of myself, especially since our classes frequently use vegetables from the “everything else” category.

The answer can be summed up in one word: Diversity.

I recently attended Food: Our Global Kitchen, the Colorado History Museum’s current exhibit.** Two juxtaposing displays really drove home the point of diversity. The first described how, at the time of the tragic Irish Potato Famine, millions of Ireland’s population subsisted largely on just one crop, the potato. To make matters worse, they relied on just one variety of potato. So when the pathogen P. infestans (a/k/a potato blight) struck in 1845, it “spread alarmingly quickly, cutting yields from that year’s harvest in half. By the next year, harvest from potato farms had dropped to one quarter of its original size.” In the ensuing famine, over one million people died of starvation.***

The second display described a very different situation across the globe, where native populations in the Andean highlands had developed nearly 4000 potato varieties over thousands of years, each capable of withstanding different diseases, pests, water availability, soil conditions, etc. So even though P. infestans is believed to have originated in Peru, the Andean region was spared its devastation.***

My great grandmother was a Potato Famine emigrant, so these displays really left me shaken. Monoculture, the practice of planting acres and acres with a single variety of a single plant, leaves us so frighteningly vulnerable–just one disease from disaster. Sadly, we haven’t learned much. Not many years after the Irish Potato Famine, American farmers continued planting fields upon fields with just a few varieties of potatoes. These became an “ocean of breakfast” for the next potato scourge: the Colorado potato beetle, which has been a continuing pest epidemic ever since, kept in check only by massive and multiple applications of pesticides.

What’s to save us? Diversity. It’s the “technology” Nature has always deployed to keep disease and pests in check. Faced with a riotous mix of species and varieties, insects and pathogens can’t multiply and adapt to dangerous levels.

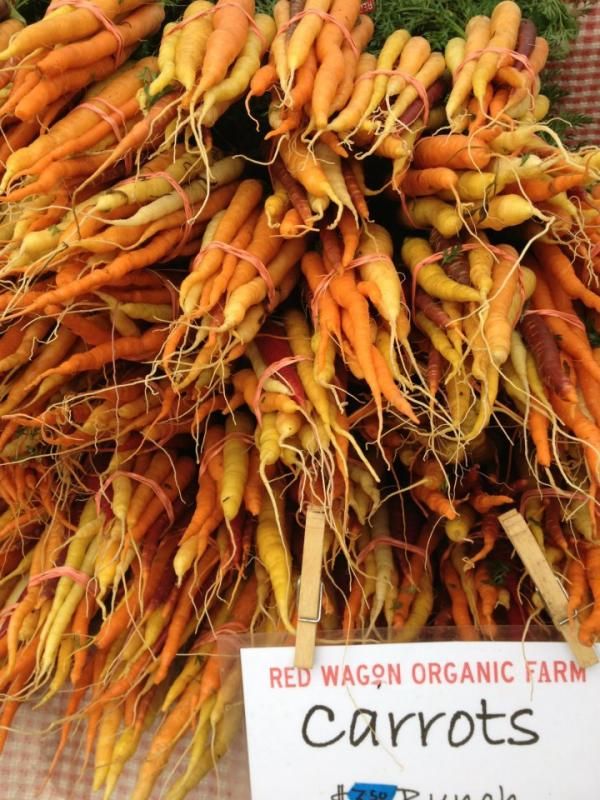

Which brings us back to turnips, kohlrabi and radishes. The more odd things on our farms, the less we are vulnerable to massive crop failures. And should pests or hail or a water shortage bring down one crop, there’s a good chance the damaging condition will have little or no affect on other crops or varieties. Last year, for instance, our CSA farm was hit by fury of hail that sheared the tops off most crops–but all the root crops were safely buried in the ground. So we rued the loss of Monroe’s famous melons, but cheered at the bounty of carrots, potatoes, beets and celeriac.

Diversity yields benefits on a personal level, too. As we eat a greater variety of foods, our bodies benefit from a wider range of nutrients. In fact, Jacquie, our CSA farmer, says this is an important reason for including vegetables from the “everything else” category, i.e., so members get a chance to try and benefit from new foods. And there’s nothing like a variety of tastes–from the sweetness of peaches to the earthiness of turnips–to create a dish with deep, well-rounded flavor.

Finally, many “odd” produce varieties are what grow best in Colorado. While finicky tomatoes and cucumbers can only be grown in our hottest months, sturdy crops like kale, chard, and yes, radishes, kohlrabi and turnips, can be grown in our chilly, unpredictable springs and autumns as well. So while waiting for the hot weather crops to (finally) produce, several rounds of cold-weather crops can be harvested and eaten–and many can be stored through the winter months.

In a world where easy and familiar vegetables are shipped in to your grocery store no matter the month, it’s easy to ignore the odd vegetables. But perhaps you want to help transition us to an environmentally sound, resilient food system, where tomatoes aren’t shipped in from places 1000 miles away and we aren’t dependent on drought-ravaged California for 90% of our food supply. One of the best ways to contribute is also one of the easiest: simply buy, use and create demand for the odd vegetables.

And don’t worry about the taste. Over time, our taste buds grow and develop so that we come to treasure the “unique” flavors of each member of the vegetable kingdom. Our classes are a perfect way to gain some exposure, experiment and learn tricks and tips to make the odd vegetables a natural part of your diet. And see the following posts on How to peel and cut a kohlrabi, quick ideas for using kohlrabi, and a recipe for Slow Cooker Kohlrabi Gratin.

Notes

*”CSA” stands for Community Supported Agriculture. Having a CSA is essentially like buying a one-season share in a local farm; in return, you get a box of the farm’s produce harvest each week.

** Food: Our Global Kitchen is open through September 1; well worth a trip to downtown Denver

*** Information drawn from Smithsonian.com, Scientists Finally Pintpoint the Pathoget that Caused the Irish Potato Famine, May 21, 2013; http://cipotato.org/potato/ and Smithsonian.com, How the Potato Changed the World, November, 2011.

1 thought on “Turnips, Kohlrabi, Radishes and Other Odd Vegetables”